PhD Dissertation

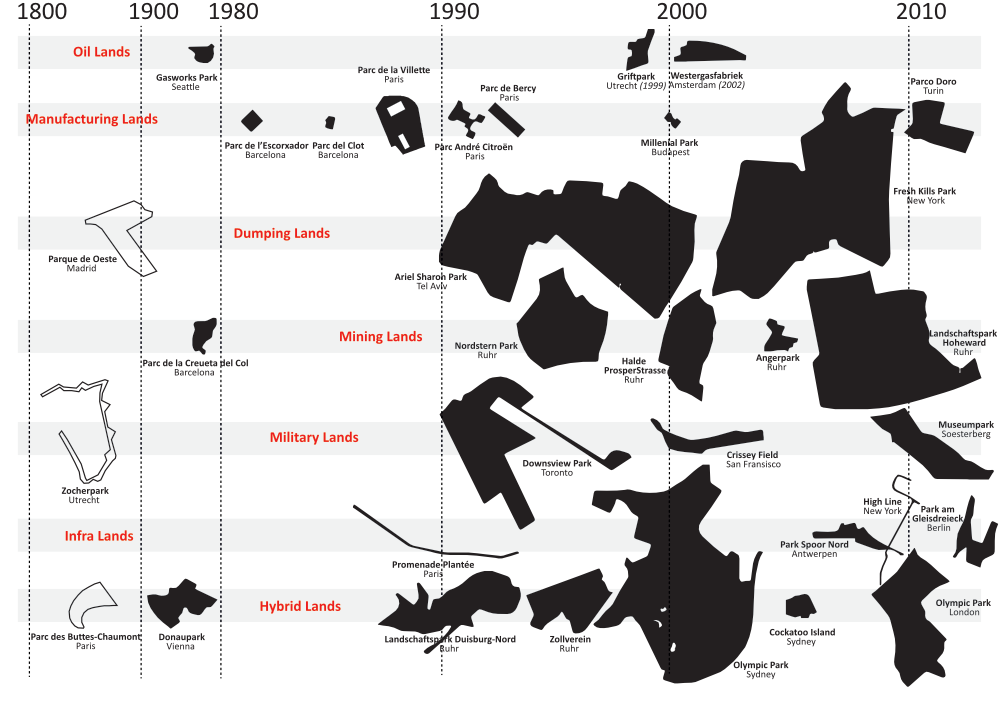

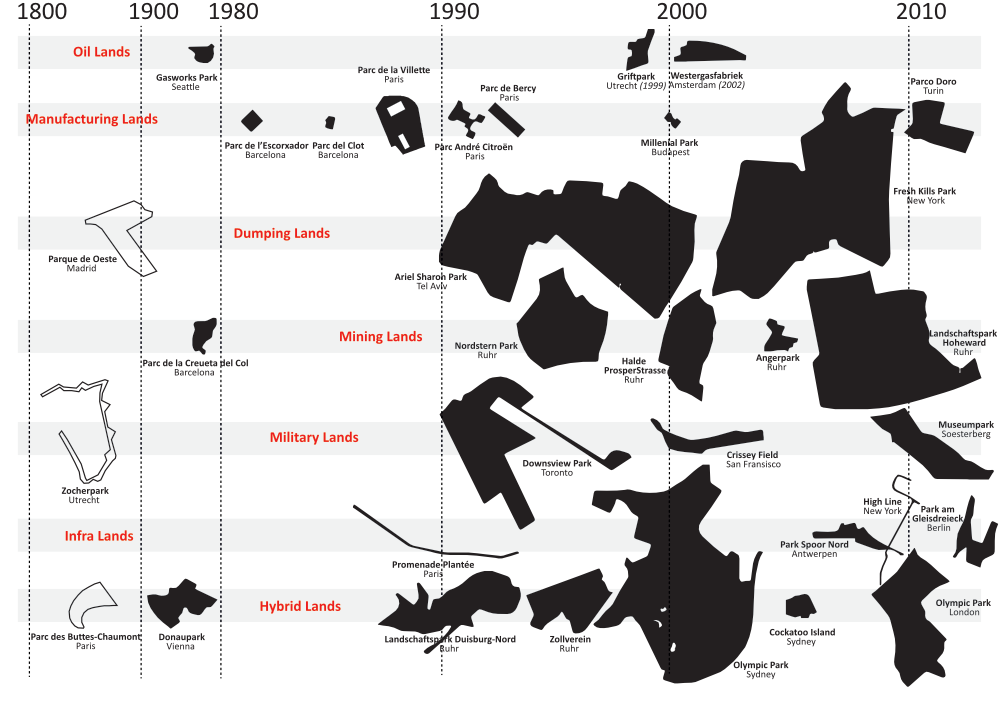

My research is entitled Transformation in Composition: Ecdysis of Landscape Architecture through the Brownfield Park Project 1975-2015. It enlarges on the notion of composition in landscape architecture by building on the ‘Delft Method’, which elaborates composition as a methodological framework for landscape design. At the same time it takes a critical stance in respect to this method in response to recent developments in landscape architecture such as the site-specificity and process discourses.

The notion of composition is examined from a historical, theoretical and lexical perspective, before turning to an examination of the brownfield park project realized in the period 1975-2015. These projects emerge as an important laboratory and catalyst for developments in landscape architecture, whereby contextual, process, and formal-aesthetic aspects form central and inter-related themes. The thesis of this research is that a major theoretical and methodological expansion of the notion of composition can be distilled from the brownfield park project, in which seemingly irreconcilable paradigms such as site, process and form are incorporated.

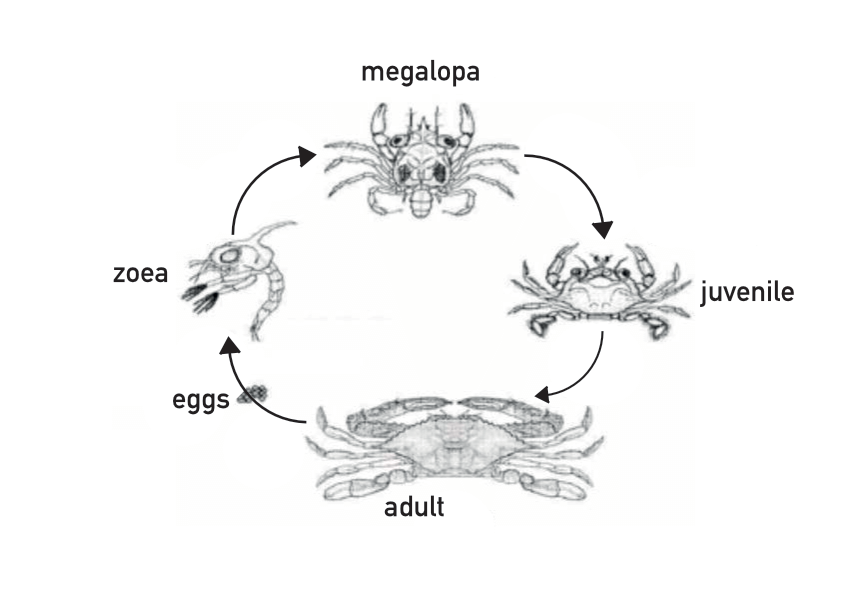

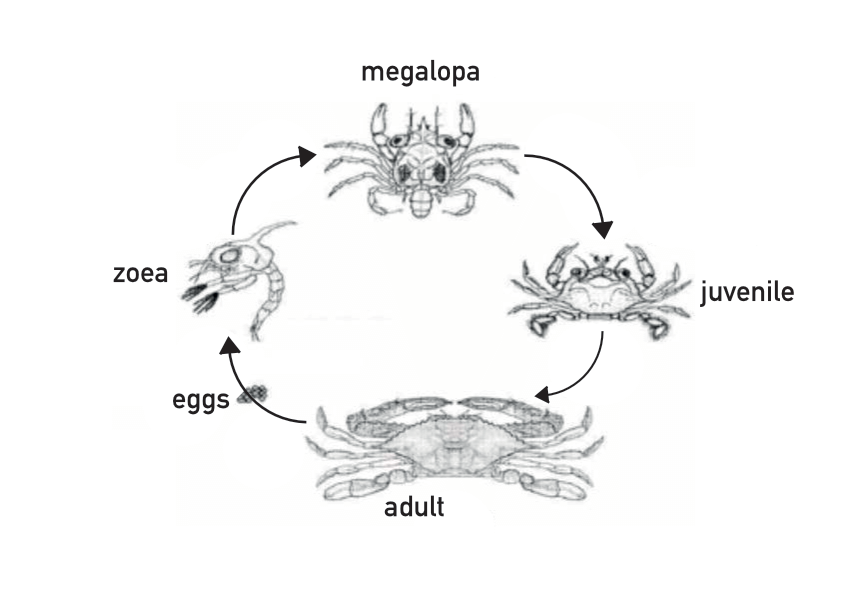

By extension, the study propositions a ‘radical maturation’ of the foundations of the discipline in the period 1975 – 2015 via the brownfield park project. A metaphor for this process is offered by the phenomenon of ecdysis in invertebrate animals, whereby the growth from juvenile to adult takes place in stages involving the moulting of an inelastic exoskeleton. Once shed, a larger exoskeleton is formed, whose shape and character is significantly different to its forebears.

In the slipstream of these findings, the research sheds new light on the shifts in the form and content of the city itself in this period, and the agency of the urban park in the problematique of urban territories. Finally, in examining the impact of de-industrialization on the contemporary urban realm, it proposes a major revision of abiding definitions of ‘city’ and ‘nature’, and the paradigms of modernity that backdrop them.

The public defense ceremony is on the 12th of June 2018 in Delft, after which the dissertation will be available as an open access publication on https://journals.open.tudelft.nl/index.php/abe

I wrote this essay for the book Lost Landscapes LOLA landscape architects brought out on winning the Rotterdam-Maaskant prize for Young Architects 2013. The philosophical and ethical dimensions of a radical planting concept such as LOLA proposed for the Singel Park in Leiden opens up the pandora’s box of confusion about what we think of as ‘nature’ and ‘natural’. Time for a reality check – or as Dirk Sijmons would say, “Welcome to the Anthropocene”.

RE-VISIONING NATURE

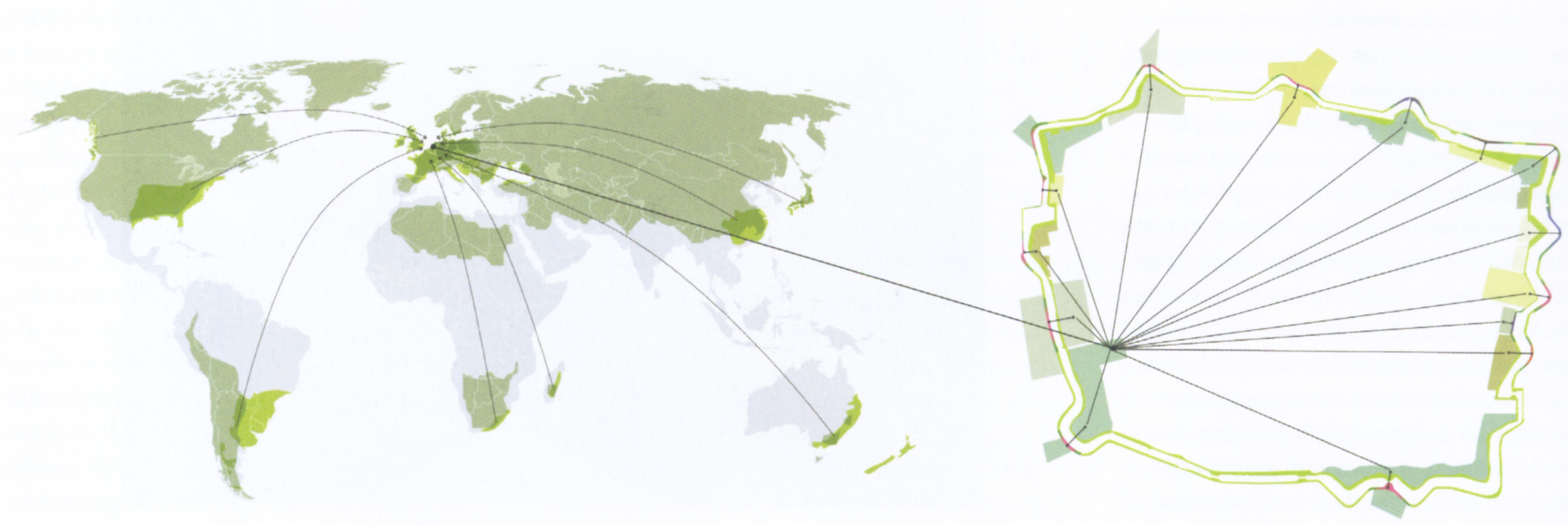

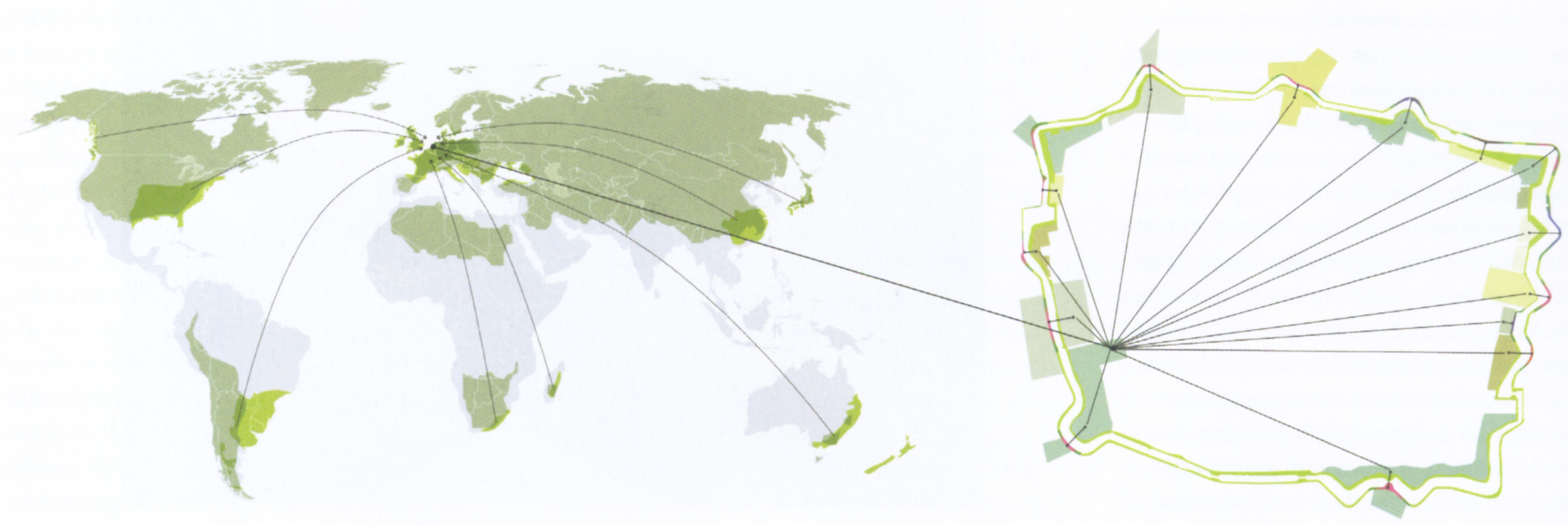

Against the rousing backdrop of its immense and diverse man-made landscapes, one would expect Dutch landscape architects to have developed a similar breadth of thinking on the concept of nature, their relationship to it, and the ways to elaborate on these ideas with design. More so given the rise of interest in nature internationally in recent decades, and the contribution by the Dutch with their own unique version of nature conservation: the design and construction of new natural areas. Moreover, the design of numerous parks, gardens and public open spaces here in the last few decades would be reasonably expected to have also provoked engagement with developing scientific, philosophical, aesthetic and ethical issues on nature. After a brief flurry of discussion during the launch of the ecological ‘mainframe’ for the Netherlands (EHS) in the 1990s however, things went quiet. Welcome news then, that a landscape design office such as Lola is engaging with nature on different levels in their work, such as in the Singel park competition in Leiden, won in 2011 together with Bureau Karst from Switzerland. A central idea in the scheme is a planting concept accentuating the diversity of green spaces around this six-kilometre long linear park. Under the theme ‘cosmopolitan nature’, their idea is to showcase plant communities from climatic zones similar to that of Leiden, from North and South America, South Africa, Madagascar, Australia, China and Japan. The idea however, was not greeted with the same enthusiasm as the rest of the scheme. Why use ‘alien’ species? Shouldn’t the design be using plants that were native to the area?

This response is grounded concepts such as biogeography, which divides plant species into specific plant districts around the world, determined by their abiotic, biotic and cultural conditions. Adepts of biogeography promote the use of plants from the geographic regions in which the project is located, a movement that has increasingly influenced garden and landscape design in the last hundred years. Lola’s scheme challenges the principles of biogeography initially for aesthetic reasons, but also questions fundamental concepts in biogeography. To begin with, how does one decide what is a ‘native’ and what is an ‘alien’ species? From the perspective of evolutionary biology the concept of native and alien is certainly fluid. Plants and plant communities are anything but static, developing and adapting to different circumstances over millennia. Native or alien thus depends on when one looks at the deep-time clock. Moreover, native and alien is also a question of cultural history, particularly in the Netherlands. Many of the plants we now consider native, migrated here in the holds of cargo ships or war fleets or were introduced by new cultures, first from Europe, later elsewhere. Dutch nature has been termed a ‘mosaic of memories’ by the biologist Piet Schroevers, a curious inter-relationship between shifts in biodiversity and periods of discovery, trade and contact between the Netherlands and the rest of the world.[i]

Lola’s planting concept is a very literal demonstration of this mosaic, but also has an important ethical component to it. If part of the reasoning for planting is that we are respecting an organism’s intrinsic value, on what basis do we decide that plants only ‘belong’ in one particular district and not in another, and thus which organism has more value than the other? And if we were to apply the same rules to humans, wouldn’t we certainly be infringing on fundamental human rights? Suddenly a scientific concept starts to display dubious political undertones; Jewish people were prohibited from gardening with native plants in Nazi Germany, a doctrine linked to the concept of biogeography. Lola’s scheme also exposes broader problems in mainstream ecological theory and biodiversity thinking in relation to the nature/culture duality and our cultural and urban landscapes. The correlation between biodiversity loss and environmental quality and urbanization for instance, is highly dependent on geographical and political contexts; while population growth and urbanization in third world countries is certainly detrimental to biodiversity, in many first world countries the opposite is true: biodiversity in many European cities now exceeds that of most non-urban territories in mainland Europe.[ii] Urban biodiversity stems in a large part from hybrid forms of nature in urban environments – ‘cosmopolitan’ nature.

More fundamentally, by taking on mainstream ecosystem principles we choose to narrow our focus to the understanding and mitigation of urbanizing societies’ effect on ecosystems, thereby perpetuating a fundamental distinction between man and nature in our approach. Without discounting that there are obvious problems resulting from the sprawl of urban areas and growth of urban populations, the continued distinction between man and nature is increasingly problematic. We are now seeing that the divide between man and nature is eroding and that hybrids are appearing (for example, the question whether climate is a natural system or a co-production of human and natural influences) and that inter-dependencies are being rediscovered, making way for a new consensus: that society and nature may still be distinguished from each other but not separated. Indeed, the illusion of separation is perhaps in itself the causes of many pressing global problems.[iii]

[i] Schroevers, P. 1998, Oorden van Onthouding, Rotterdam, NAI press.

[ii] Gilbert, O. L. 2005, Urban ecology: Progress and problems. Journal of Practical Ecology and Conservation Special Series, 4, 5–9.

The April 2012 edition of Atlantis’ – the magazine of student association POLIS at the TU Delft – explores the relationship between city and landscape. I wrote an introductory article exploring the oxymoron ‘urban landscape’ and the common ground between Urbanism and Landscape Architecture. The push to merge the two fields might be an accurate diagnosis of the contemporary city, but is not necessarily the solution to it.

Contributors to the edition came from Edward Soja, Dirk Sijmons, Jaap van den Bout, Geoff Manaugh, Daniel Jauslin, Alexander Wandl and Maurits de Hoog; plus interviews with Hans de Jonge, Mitesh Dixit (OMA), Matthew Skjonsberg (West 8 ) and the Korean landscape professor Jonghyun Choi. Read them all at http://polistudelft.nl/atlantis/22-4-3/

For someone unfamiliar with contemporary discourses within the building sciences, the theme of this Atlantis issue would appear to be something of an oxymoron. The term ‘urban’ surely infers the spatial, organizational, political, social and cultural characteristics of city, a very different notion than the rural or natural environments inferred to by the term ‘landscape’. This paradox is not necessarily restricted to outsiders: within the faculties of the building sciences ‘urban’ and ‘landscape’ are separate and distinct disciplinary traditions. Both fields of enquiry arise from – and are connected to – independent arenas of theory and praxis. The traditional pursuits of these two fields however – the understanding, ordering and design of cities and landscapes – are becoming more and more urgent as time goes on and as such, their legitimacy as independent disciplines is unquestioned. The linguistic union of the two terms therefore, has nothing to do with disciplinary deterioration which commonly herald these kinds of mutations, and everything to do with the pursuit of knowledge and tools to understand and act in the increasing elusive contemporary city – of which more later. Firstly, a little etymology and history.

The paradox in the term ‘urban landscape’ is linguistically speaking, less strange than it at first seems. To begin with, there are important etymological links between landscape terms such as garden and urban terms such as town. The words garden, yard, garten, jardin, giardino, hortus, tun, tuin, and town, all pertain to spatial enclosure of outdoor space. Landscape – a term related to garden and originating from the appreciation of created or cultivated land – also has related connotations of inclusion and entity. More importantly, the appreciation of landscape and its depiction as outdoor space is an invention of the city; the perception and depiction of land as landscape first appeared in the artistic milieu of urban society during the Renaissance [1]. It is no coincidence therefore, that this very same urban society was responsible for the first landscape architectural creations in the villas urbana around Rome and Florence in the same period [2]. The term ‘urban’ and ‘landscape’ can thus be argued to be inter-dependent, or perhaps more extremely put: without the city there would be no landscape. In the same way one can claim that without landscape there would be no city. The topographic and productive characteristics of land(scapes) have historically determined where cities arise – as well as having an effect on their form, size, shape and wealth. They also determine for a large part the character of the city itself through the configuration and character of its public open spaces, the figure ground of the city and even the way the city develops and changes. These modes of landscape within the urban realm are another important reason behind the development of the term urban landscape as an independent arena of praxis and enquiry. They also happen to form a useful trinity of sub-themes within the field, which roughly span the theoretical and practical breadth of the theme: landscape within the city, landscape beneath the city, and the city as landscape.

Landscape within the city

The sub-theme landscapes within the city focuses on urban public space – exploring the spatial and social problematique of the physical network of public (open) space in contemporary cities. The addition of landscape (and landscape architecture) to the problematique reflects the increasing complexity and crisis developing in public space and the public domain. The ‘decline’ of urban space in general and its widely accepted causal ‘isms’ – individualism, capitalism, neo-liberalism – are demanding an increasingly sophisticated arsenal of tools to understand, order and operate with. In theoretical and philosophical discourse, the public domain – and its physical counterpoint public space – has always been understood as an urban problem, but new insights from the perspective of landscape have proven – at least from a theoretical point of view – extremely fertile [3]. Landscape has a lot to offer public space and the public domain: a ‘grounding’ of urban communities in a physical and historical landscape context, visual and spatial multiplicity within the architectonic confines of the city, infrastructures for social and cultural interaction and the emotive and experiential qualities of nature within an urban environment. The remarkable success of High-line park in New York also demonstrates the value of ‘landscape’ to the public space discourse in praxis. In this (and other) projects, landscape has also proven itself as a factor in the successful regeneration of urban neighborhoods.

Figure 1. High-line Park, New York. Photo: James Corner Field Operations.

Figure 1. High-line Park, New York. Photo: James Corner Field Operations.

Landscape beneath the city

A second sub-theme – the urban landscape beneath the city – covers a much broader field of exploration: that of the role of a previous or underlying landscape in (re)defining the spatial fabric of cities. Growing criticism of the tabula rasa thinking of modernism in the second half of the 20th century lead to the search for a new repertoire to understand and give form to cities. Already in the 1960’s, Vittorio Gregotti argued for an ‘anthropo-geographic approach’ to urbanism, a return to the topography and ecology of a region to inform the urban fabric [4]. Studies in the Netherlands such as Frits Palmboom’s analysis of Rotterdam as urbanized landscape prompted a return to landscape context and underlying landscape characteristics such as topography, geomorphology, drainage patterns, vegetation types and historical settlement forms in the layout of new urban areas here. This was not necessarily new -there are important historical precedents of this. The proposal to develop Boston around a necklace of parks along the Charles river at the end of the 19th century is one of the first – and most extensive – examples of an ‘urban landscape’ project. The exploration of the evolving relationship between city and landscape and the role of the landscape beneath the city, is explored in a new publication Metropolitan Landscape Architecture by Clemens Steenbergen en Wouter Reh (reviewed in this issue by Berrie van Elderen). The rediscovery of the relationship between geomorphological and cultural landscape layers and ensuing urban patterns in pre-modern cities became the leitmotif for a discipline in search of a new beginning. This approach was also posited on the notion of process and continuity in city form – urbanization as a stage in the perennial transformation of landscape.

The advantage of landscape beneath the city has also increased since its introduction as framework for spatial planning on a regional scale. Landscape in countries such as the Netherlands is increasingly identified as the primary ingredient of spatial planning ideologies such as longue durée: the establishment of a permanent spatial framework for all manner of dynamic processes, including urbanization [5]. Recent large-scale schemes using longue durée include Meerstad in Groningen (2005) and the Wieringerrandmeer in North Holland (2005) drawn up by Bureau Hosper. Curbs in public spending and the decentralization of spatial policy poses a serious threat to strategies such as longue durée but these – and the financial, climate, energy and food crisis – can also be argued as reasons to step up the use of longue durée landscape; it may be all we have left.

Figure 2. Regional Development Model, Groningen Meerstad, Bureau Hosper.

City as landscape

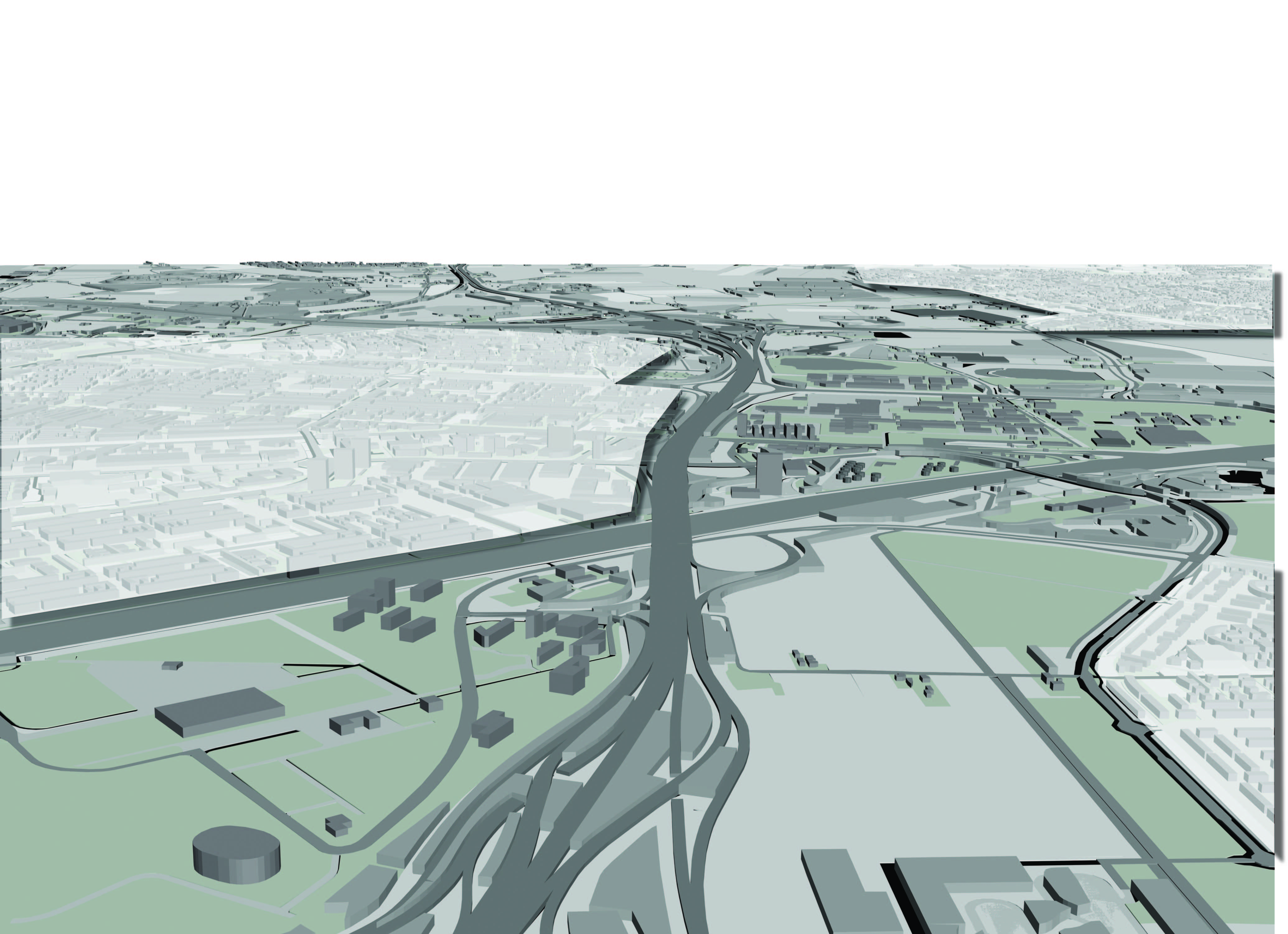

Undoubtedly though, the most pregnant – and contested – interpretation of the term ‘urban landscape’ is the notion of city as landscape. At the start the 21st century, the legitimacy of the notion that city and landscape have become one – at least in geographical terms – has become indisputable. Since the middle of the last century an increasing number of researchers have been involved in charting and analyzing this transition; each research conference and publication seems to come up with a new term to describe the phenomenon. While the idea of the city may still conjure up images of a coherent ensemble of built forms, spaces and programs, the city is clearly becoming progressively less and less an architectonic artifact and more and more a patchwork of urban fragments interwoven with – and infused by – landscape [6]. This process is not new. As early as the early 19th century, the compact and orderly urban tissue of the city fell prey to forces of growth and change, which progressively eroded its architectonic cohesiveness and loosened up its characteristic homogeneity. Landscape crept as it were, into the cracks in this ever-expanding organ.

Developments in the same period point to a parallel process of the dissolving of the ideals and values associated with the classical city form. The former clarity and definition of the collective order of the city has given way to a loose-knit aggregation of urban territories in which the distinction– and relationship – between public and private has become anything but clear. Responses to this condition took form in the garden city movement and later schemes such as Frank Lloyd Wright’s broad-acre city. Subsequent approaches to understanding and giving form to the city as landscape appeared in theoretical and experimental projects in the work of Archigram and Reyner Banham’s pioneering study of Los Angeles, The Architecture of four Ecologies.

Towards the end of the last century these theoretical forays also took root in ‘real’ projects such as Chasse terrain by OMA, Borneo Sporenburg by West 8 and Muller pier by KCAP. Pioneering (but as yet unverified) ‘taxonomies’ of the concepts used (grid, casco, clearing and montage) position them squarely within the landscape idiom [7]. These techniques have since also ‘landed’ in a number of mid-size urban developments in the jumelage between city and landscape. Thirty-five recently realized plans of urban living in the landscape in the Netherlands has recently been published in a landmark study by the offices of Faro, H+N+S and Palmbout [8].

Figure 3. Borneo Sporenburg development, Amsterdam. Photo: René de Wit.

The rapidly changing position of landscape in the discourse on the contemporary city gained further academic (and international) momentum with the introduction of the term Landscape Urbanism in 2006. In this ‘manifesto’, landscape supplants architecture as the essential organizing element for the contemporary (horizontal) city. Landscape is also seen as the tool to comprehend and order urban development because they had come to resemble each other as system and process: the city now changes, transforms and evolves as a landscape [9]. As a medium, landscape is purported to be capable of responding to transformation, adaptation and succession, making it more analogous to contemporary urbanization and better suited to the open-endedness, indeterminacy and change of future cities [10]. The modern urban condition is defined by indeterminacy and change: the city is in a state of flux, always on its way to becoming something else. The processes of urbanization can be seen as a kind of human ecology: a complex that includes language and technology, and that produced and continues to produce spatial organization as an emergent order {11]. Whether it be the growth and seasonal dynamics of living material or the more abstract processes of temporality, transformation, and adaptation, landscape – and landscape ecology – are championed as tools to understand, order and act with. Instead of concentrating on formal objects, dynamic relationships and agencies become the subject of study and design [12].

The relationship between landscape and city, between landscape architecture and urbanism, and between landscape and urban ideologies is undoubtedly deepening. Contemporary academic discourse is either pushing for a merger of urban and landscape disciplines, or calling for further disciplinary specialization. The re-emergence of landscape comes because of its potential to embrace urbanism, infrastructure, strategic planning and speculative ideas, a quality, however, that is by definition rich and diverse, arising from a range of sometimes-conflicting perspectives. At the same time many new directions are simply reformulations of perennial concerns of the both disciplines. The oxymoron created by the terms ‘urban’ and ‘landscape’ is justifiable and irrevocable, but we should tread carefully before we go mixing the symptoms with the cure.

[1] Ton Lemaire, Philosophy of Landscape (Amsterdam:Ambo publishers, 1970)

[2] Wouter Reh & Clemens Steenbergen, Architecture and landscape – The design experiment of the Great European Gardens and Landscape (Basel, Berlin, Boston: Birkhaüser, 2003)

[3] James Corner, Recovering Landscape: Essays in Contemporary Landscape Architecture (Princeton: 1999)

[4] Vittorio Gregotti, ‘La forme du territoire’, in l’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui no. 218 (1981)

[5] Dirk Sijmons, Regional Planning as a strategy, In: Landscape and Urban Planning (18) 265-273 Elsevier Science Publishers, 1986

[6] Bernard Colenbrander, De verstrooide stad (NAi Uitgevers: Rotterdam, 1999)

[7] Marcel Smets, ‘ grid, casco, clearing, montage’ in About Landscape Edition Topos (Basel, Berlin, Boston: Birkhaüser, 2002)

[8] Faro, H+N+S, Palmbout, Landschappelijk Wonen, (Wageningen Blauwdruk: December 2011)

[9] Kelly Shannon, ‘From Theory to Resistance: Landscape Urbanism in Europe’, in The Landscape Urbanism Reader (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006)

[10] Charles Waldheim, ‘Landscape as Urbanism’, in The Landscape Urbanism Reader (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006)

[11] Dirk Sijmons, The City and the World, Inaugural address, TU-Delft 09 december 2009

[12] René van der Velde, ‘Landscape Urbanism in the dutch design tradition’, in 4th International Seminar on Urbanism and Urbanization (ISUU), TU Deft, Holland (09/2007), pp 154-162.