The sixth edition of the International Architecture Biennale runs until 24 August 2014 in the Kunsthal in Rotterdam. Curator Dirk Sijmons asked me to put together an exhibition on the representation of nature in urban parks, drawing on work from my PhD research into ‘Transformation Parks’ on brownfield sites. Museum park, which lies next to the Kunsthal, was not part of my research but is an excellent example of nature representation so we decided to include it in the exhibition. As it happened this was a timely decision as the debate on Museum park has since flared up with the proposal for a new depot building by MVRDV in the northern end of the park. Here is a short summary of the exhibition, but visiting the Biennale itself is of course a much better option.

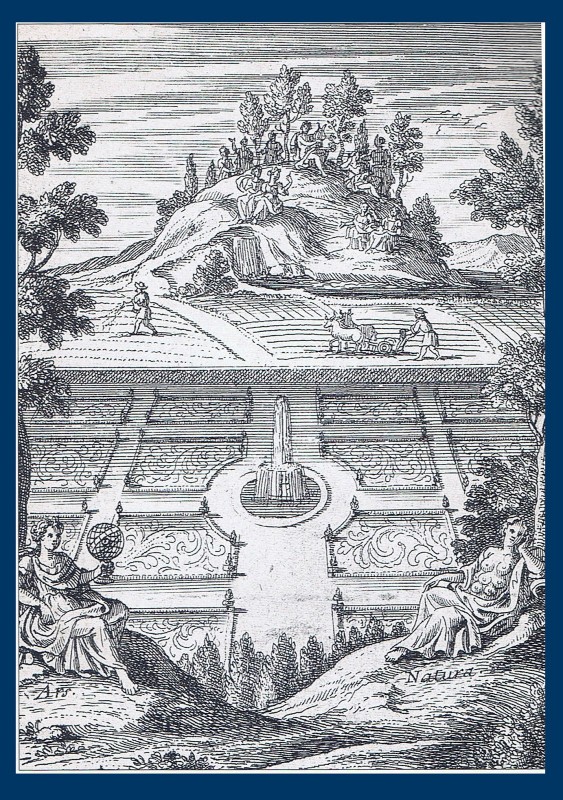

Envisioning nature is a central theme in urban parks. The first visions of nature are attributed to Cicero, the roman philosopher who discusses two different forms of nature: the wilderness – the realm of the gods untouched by human hands, and the field – the meadows and ploughed fields, orchards, terraces and rural settlements made by man. A third vision of nature – the garden – was added to Cicero’s pair in the Renaissance, which combines both the wilderness and the field in a new way.

The three natures are represented in the 18th century frontispiece to Curiositez de la Nature et de l’Art. A formal parterre represents the first nature of the garden in the foreground, with the second nature of agricultural fields in the middle distance. A natural hillock with a gushing spring and a stand of trees represents the first nature of the wilderness in the distance.

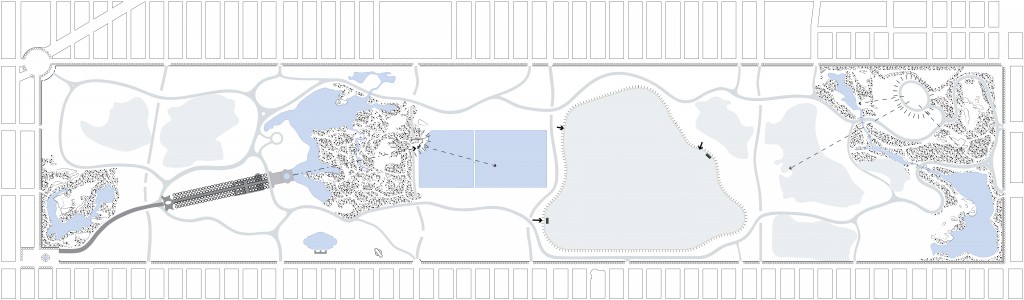

These three visions of nature – wilderness, field and garden – formed the basis for the representation of nature in nineteenth century urban parks such as Central Park in New York. Olmsted placed the ‘wilderness’ (first nature) in the extremities of the park, separated by large expanses of ‘field’ (second nature), with the ‘garden’ (third nature) expressed in small elements and details such as the ornamental pond, the reservoir walk and the ensemble of entrance, mall, terraces and belvedere.

Three natures in the composition for Central Park, New York. Design: 1857. Landscape Architect: Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903)

Drawing from: Reh, W. & Steenbergen, C. (2011). Metropolitan Landscape Architecture: Urban Parks and Landscapes. Amsterdam: Thoth.

In the course of the twentieth century, the representation of nature in parks became increasingly sidelined in favour of social and recreational ideals but from the 1970s on a new generation of designers returned to the representation and expression of nature in park designs. In his winning design for the La Villette competition, Bernard Tschumi proposed a garden walk connecting twelve themed gardens spread through the park demonstrating a return of third nature representation in the urban park.

Axonometric gardens, garden walk, avenues, folies and galleries, Parc de la Villette Design: 1982.

Architect: Bernard Tschumi

Drawing: Transformation Parks, PhD research René van der Velde, TU Delft (in progress)

Tschumi also experimented with the overlaying of disparate organizing systems, an approach which embodied the city as a form of ‘wilderness’ (first nature).

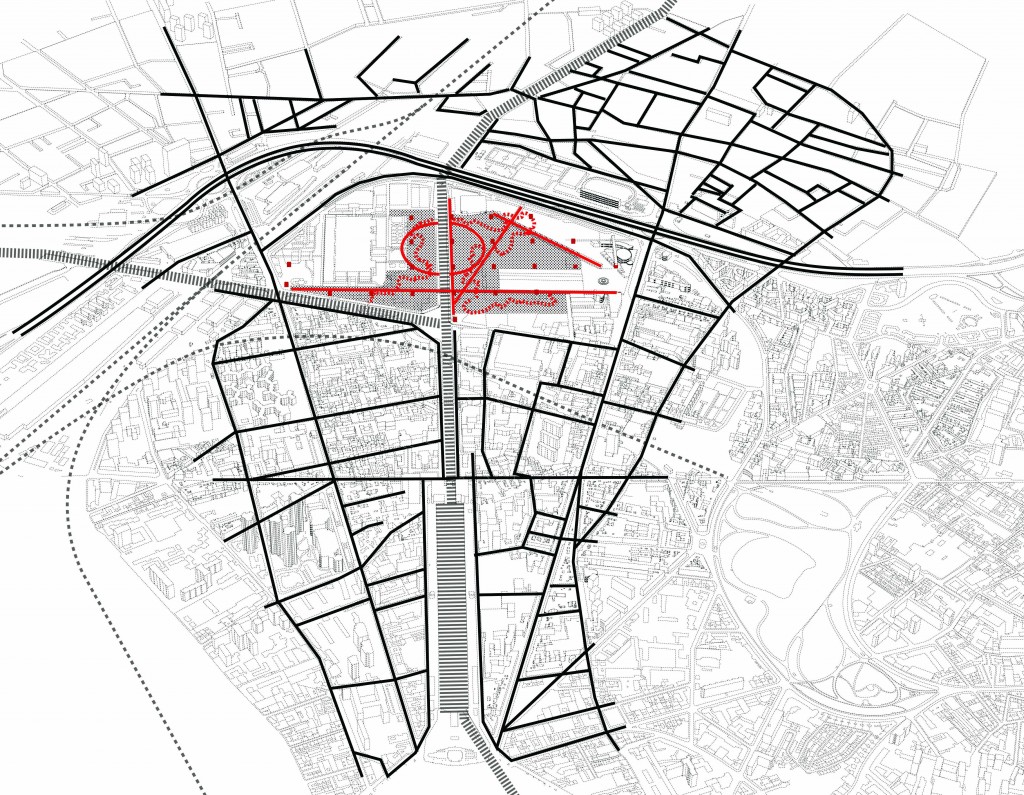

Resemblance of contextual geometries to park geometries, Parc de la Villette.

from: Transformation Parks, PhD research René van der Velde, TU Delft (in progress)

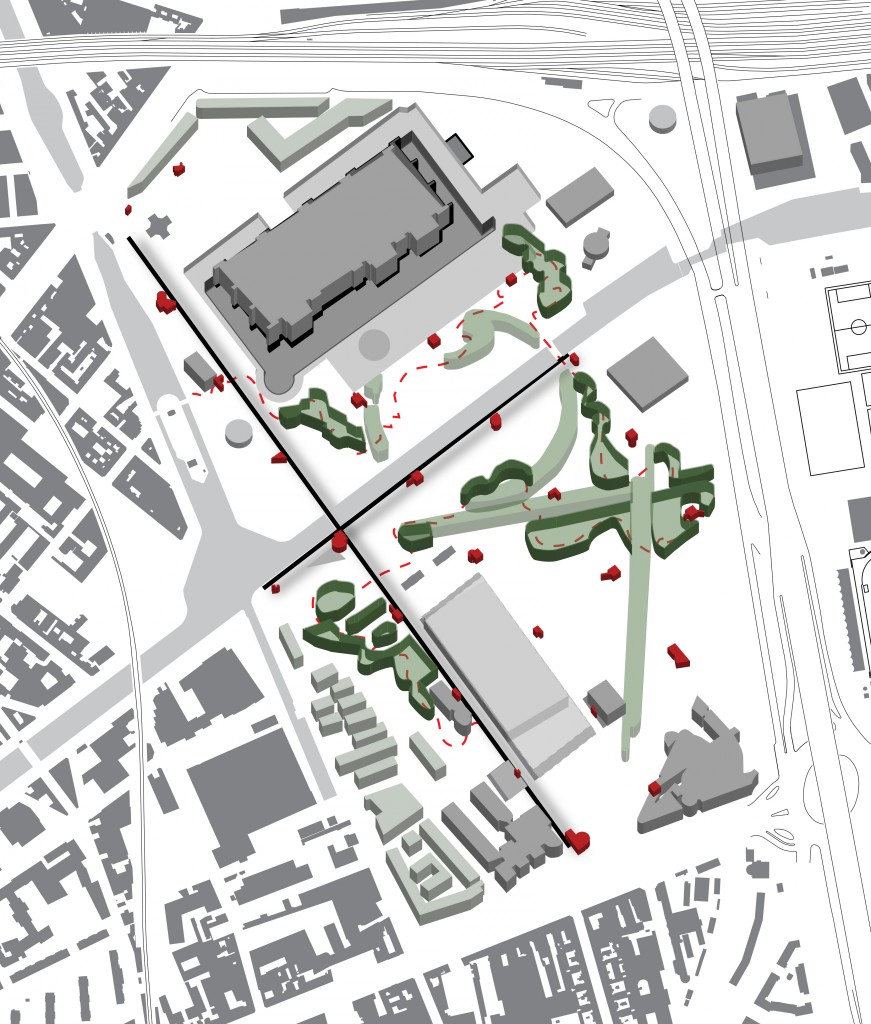

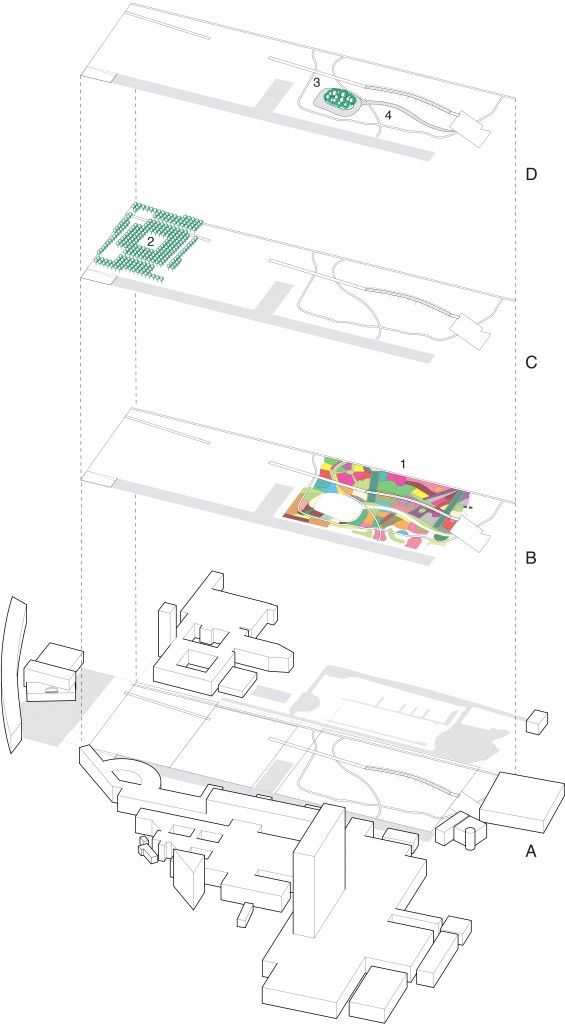

The representation of the ‘three natures’ came back in force in the design for Museum Park – but in a novel new way. Koolhaas, Brunier, Blaisse, Adams, Lammers and Mescherowsky designed a composition was a series of consecutive ‘rooms’ linking the surrounding musea. The first ‘room’ was planted out with a grid of white-stemmed apple trees, and the third room was a romantic sensory garden with a ‘mountain stream’ and ‘wild island’. The white-stemmed apple trees depict the second nature of the agrarian landscape, the sensory garden that of third nature, and the meandering stream with lake and island depict the first nature of the wilderness. One of the essences of the composition is that all three natures are present. Take one away and the concept (and composition) dissolves.

Exploded axonometric view, three natures in the composition for Museum Park, Rotterdam based on the 2011 renovation plan by Petra Blaisse, Nico Tillie and Chris van Duijn.

Drawing from: Transformation Parks, PhD research René van der Velde, TU Delft (in progress)

Drawing: Tim Peeters A. Groundplane

B. ‘Garden’

C. ‘Field’

D. ‘Wilderness’

Museum park is an important (international) example of the recovery of the urban park as public space typology in the contemporary city, which among other things embodies – and experiments – with notions of nature in contemporary urban societies. Alterations or transformations of the park need to acknowledge and address these qualities– or come up with something better!